Crawford was the key to the whole deal. To audiences of the ’50s, a movie was only as enticing as its star, and Johnny Guitar had one of the brightest. Today, most people think of Crawford as the notorious “Mommie Dearest,” subject of the scandalous tell-all book written by her adopted daughter, Christina, in 1978. The memoir, turned into a campy 1981 film starring Faye Dunaway, chronicled the alleged terrors Crawford’s children endured at the hands of a ruthless, alcoholic, child-abusing mother more concerned with her own fading career and love affairs than their well-being and happiness. These revelations (which have been disputed by two of Crawford’s other adopted children) now overshadow the achievements of her career, which stretched from 1925 to 1972.

Such skeletons in the closet were inconceivable for moviegoers in a pre-TV era when Crawford was the very definition of a movie star: beautiful, glamorous, sophisticated. In the eyes of her public, she was a goddess; behind the scenes, she had a reputation as a driven, ambitious, perfectionist who was incredibly competitive. Paradoxically, she also could be warm and cordial — when she wanted to be.

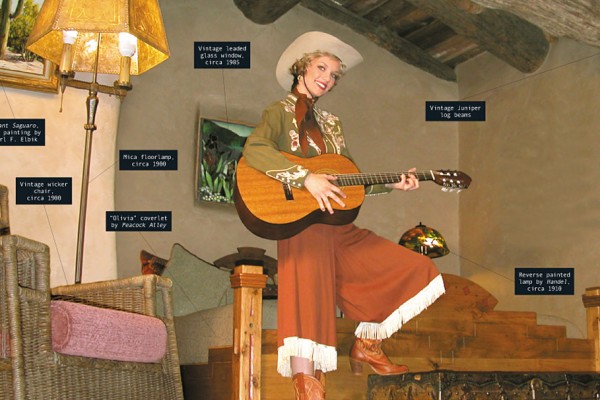

Like all image-conscious movie queens then and now, she retained contractual control over how she would be photographed. Before Johnny Guitar‘s production began, she approved Oscar-winning director of photography Harry Stradling, cinematographer for classics such as Easter Parade in 1948 and 1964’s My Fair Lady, in a contract rider dated Sept. 22, 1953 (see document at right). At the same time, she OK’d the use of Republic’s own overwrought “Trucolor by Consolidated” as his film process, a decision that unwittingly stamped the movie with a surreally stylized oversaturation of color. Combined with its ’50s-style art direction, it gives Johnny Guitar an intriguing, uniquely modern-looking “old West.” Filmmaker Jim Jarmusch (director of Dead Man, shot in Sedona in 1995) once called Johnny Guitar “the only western that looks like it was shot inside a ’50s ski lodge.”

The man who called the shots, director Nicholas Ray, had just completed seven years under contract to Howard Hughes’ RKO Radio Pictures in 1953, and was searching for the creative freedom denied him while working for the eccentric billionaire. Ray had helmed a number of recent RKO hits, including Flying Leathernecks (1951) with John Wayne and The Lusty Men (1952) with Robert Mitchum. And Ray would spread his wings soon enough with his signature work, 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause, the teen-angst drama that made a legend of James Dean.

Ray, who took no credit for it, cowrote the Johnny Guitar screenplay with credited Philip Yordan, whose career now sits under a bit of a cloud. During the McCarthy era, he worked as a “front,” putting his name on scripts by writers who had been blacklisted as communist sympathizers; the basement of his Paris home was often filled with exiled writers working in cubicles, churning out “Yordan” screenplays. Because of this, questions about which films he actually wrote dog his legacy; listed among his credits are 1951’s Detective Story with Kirk Douglas, and Houdini (1953) with Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh.

Ray discarded novelist Chanslor’s draft of the script, which was more of a straightforward cowboy movie. Chanslor would go on to write another western novel with a lead female character, Cat Ballou, which was made into a movie starring Jane Fonda in 1965.